AMD

Can it Challenge Nvidia's Monopoly

Advanced Micro Devices (AMD) and NVIDIA Corporation are two of the semiconductor industry’s titans, each with a rich history and pivotal roles in computing. Today’s post examines their histories, business models, leadership, competitive dynamics, moats, product roadmaps, financials, and all claims are backed by credible sources which can view at end of post

Introduction

AMD’s Journey:

AMD was founded on May 1, 1969 by Walter “Jerry” Sanders (a Fairchild Semiconductor alumnus) and seven colleagues, with an early focus on logic and memory chips. Gaining a reputation for reliable, military-standard components, AMD steadily grew through the 1970s.

A major turning point came in 1982 when AMD struck a technology licensing deal with Intel to produce x86 processors, establishing AMD as a second-source for PC microprocessors. Tensions later led to legal battles (notably over the Am386 chip in 1991 which AMD had reverse-engineered), but by the mid-1990s AMD emerged as a viable competitor to Intel in CPUs. AMD’s Athlon processors in 1999-2000 achieved industry firsts like the first 1 GHz x86 CPU, and AMD pioneered 64-bit x86 computing with its Opteron and Athlon64 chips in 2003 – a strategic coup as Intel’s alternative (Itanium) faltered.

In 2006, AMD acquired ATI Technologies for $5.4B to enter the graphics processing unit (GPU) market. This gave AMD the Radeon GPU line and ultimately enabled APUs (accelerated processing units combining CPU & GPU on one chip). However, the ATI buy also burdened AMD with debt and integration challenges, contributing to financial struggles through the late 2000s. AMD responded by spinning off its manufacturing arm in 2009 (creating GlobalFoundries) to become fabless and lighten capital expenditures.

Under CEO Dr. Lisa Su (appointed 2014), AMD executed a dramatic turnaround in the late 2010s by focusing on a new ground-up CPU architecture (“Zen”). The 2017 launch of Ryzen CPUs based on Zen marked AMD’s return to high-performance computing, offering competitive multi-core chips at attractive prices. In the following years, AMD rolled out Zen 2, Zen 3, and Zen 4, achieving generational leaps in performance and efficiency that allowed AMD to surpass Intel in certain CPU benchmarks by 2020. Simultaneously, AMD’s Radeon GPUs (based on RDNA architectures) competed in the graphics market, and AMD secured wins supplying semi-custom chips for gaming consoles (both Sony’s PS4/PS5 and Microsoft’s Xbox One/Series use AMD chips).

By 2023, AMD even entered the AI accelerator fray with its Instinct MI200/300 series, combining CPUs and GPUs for high-performance computing and AI – positioning AMD to challenge Nvidia in data center accelerators. In short, AMD’s history is a rollercoaster of breakthrough innovations and near-death struggles, culminating in its modern resurgence as a broad-based processor company spanning CPUs, GPUs, FPGAs, and more.

Nvidia’s Journey:

Nvidia was founded a bit later, on April 5, 1993, by Jensen Huang (a former LSI Logic chip designer), Chris Malachowsky and Curtis Priem, with the vision of making 3D graphics accelerators for gaming and multimedia. Nvidia’s initial focus on PC graphics paid off quickly – by 1999 Nvidia had invented the term “GPU,” launching the GeForce 256 as the world’s first graphics processing unit with on-board transformation and lighting hardware. This early technical edge won Nvidia a contract to supply the graphics chip for Microsoft’s original Xbox in 2001, and later the PlayStation 3’s GPU in 2005. Throughout the 2000s, Nvidia steadily expanded from PC graphics into professional visualization and high-performance computing.

A seminal move was the introduction of CUDA (Compute Unified Device Architecture) in 2006, which allowed programmers to use Nvidia GPUs for general-purpose parallel computing. This foresight in software established a moat that would prove crucial in the AI era. By the early 2010s, Nvidia’s GPUs powered breakthroughs in machine learning – notably, the 2012 AlexNet neural network that ushered in the deep learning revolution was trained on Nvidia GPUs. Nvidia has been founder-led by Jensen Huang since inception, and his long-term bets (like CUDA and early investment in AI accelerators) positioned Nvidia to dominate the burgeoning AI market. In 2018 Nvidia introduced its RTX GPUs with real-time ray tracing and tensor cores for AI, reinforcing its technology leadership in graphics and AI. Over 30 years, Nvidia evolved from a niche graphics card supplier into a diversified platform company at the center of gaming, professional visualization, and accelerated computing for AI and autonomous machines.

Today it commands over 90% of the high-end discrete GPU market and is essentially synonymous with AI accelerators, thanks to its hardware and software ecosystem. Nvidia’s history is characterized by consistent innovation: from the GeForce and Tesla GPU families to newer architectures like Ampere, Ada Lovelace, and Hopper, each generation pushing performance and enabling new applications. This relentless innovation (coupled with savvy software development) transformed Nvidia into the world’s most valuable semiconductor company by 2023.

Connect with me

Courses

Trading View Indicators

Leadership

Dr. Lisa Su became AMD’s CEO in October 2014 during a time of financial losses, heavy debt, and declining market share. An electrical engineer with a Ph.D. from MIT, she previously worked at Texas Instruments, IBM, and Freescale before joining AMD in 2012. Her leadership drove AMD’s turnaround through bold strategies:

Invested heavily in the Zen CPU architecture despite limited resources.

Streamlined product lines and focused on high-growth markets like data center and gaming.

Prioritized high-end CPUs to compete with Intel, leading to successful Ryzen and EPYC launches.

Fostered engineering excellence and accountability, emphasizing execution.

Acquired Xilinx in 2022 (~$35B) to expand into FPGAs and adaptive computing.

Her approach, described as “dream big, but execute small,” set ambitious goals (e.g., gaining server CPU share from Intel) while delivering through consistent, incremental steps. Su rebuilt customer trust with PC OEMs and focused heavily on data center and AI growth through R&D. Under her leadership, AMD went from near-bankruptcy to record revenues and regained technology leadership in CPUs and GPUs.

Jensen Huang, Nvidia’s co-founder and CEO since 1993, is a charismatic leader known for his black leather jacket and visionary keynotes. With an MSEE from Stanford and experience at LSI and AMD, he foresaw GPUs as central to computing. His bold, long-term strategies include:

Evolving Nvidia from PC graphics to console gaming, professional graphics, and AI computing (2006-2010).

Investing in CUDA (2006) to build a software ecosystem, creating a strong developer lock-in.

Entering new markets like autonomous vehicles (DRIVE platform) and networking (Mellanox acquisition).

Focusing on AI as the new computing era, providing hardware, systems (DGX), and software frameworks.

Huang’s intense, visionary leadership ensures high execution standards, with Nvidia rarely faltering on product delivery. He forged partnerships with cloud providers and software companies to embed Nvidia’s tech broadly. Under Huang, Nvidia’s market cap reached trillions, dominating AI and GPU markets. His philosophy—“Software is eating the world, but AI is going to eat software”—drives Nvidia’s leadership in AI computing.

How They Make Money

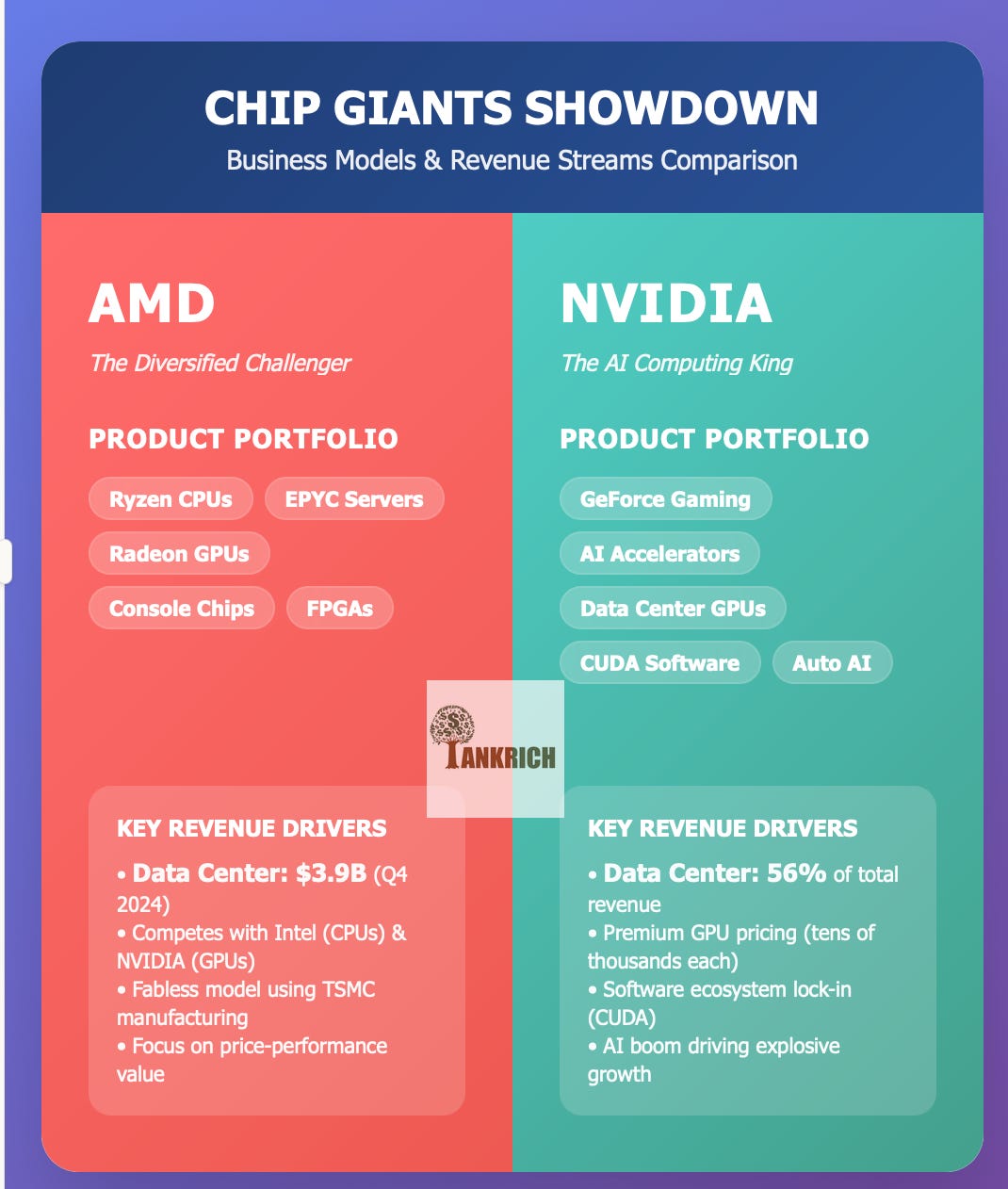

AMD is a fabless semiconductor company designing a wide range of high-performance chips, including:

PC processors (Ryzen CPUs for desktops and laptops).

Server processors (EPYC CPUs for data centers).

Graphics processors (Radeon GPUs for gaming and professional graphics).

Semi-custom chips (for PlayStation, Xbox, etc.).

Adaptive computing products (FPGAs and System-on-Chips from Xilinx acquisition).

AMD partners with third-party manufacturers like TSMC to produce these chips.

How They Make Money:

AMD generates revenue by selling these chips to:

PC and laptop makers (e.g., Dell, HP).

Console makers (e.g., Sony, Microsoft).

Cloud providers (for server CPUs and GPUs).

Graphics card partners (for gaming and professional GPUs).

The company’s profits come from offering competitive chips to gain market share from Intel (CPUs) and Nvidia (GPUs) while keeping costs low by outsourcing manufacturing. AMD’s sales are reported in segments: Client Computing (PC CPUs), Gaming (GPUs and console chips), Data Center (EPYC CPUs and Instinct AI accelerators), and Embedded (chips for networking, automotive, aerospace). The Data Center segment has grown significantly, reaching $3.9B in Q4 2024, with higher-margin server chips and AI accelerators driving recent growth.

Nvidia designs graphics processing units (GPUs) for gaming, professional visualization, and parallel computing tasks like AI and scientific simulations. Their products include:

GeForce/RTX GPUs for gaming PCs and workstations.

Data center GPUs (e.g., A100, H100) for AI and high-performance computing.

Automotive chips (Drive platform for self-driving cars and infotainment).

Networking hardware (from Mellanox acquisition).

Nvidia also provides software like CUDA, AI libraries (cuDNN, TensorRT), and graphics frameworks to enhance GPU functionality and lock in developers.

How They Make Money:

Nvidia earns revenue by selling:

GPU cards for gaming and professional visualization.

High-end data center GPUs to cloud providers (each chip costs tens of thousands).

Systems like DGX servers for AI.

A small portion from software licensing and services.

Their business segments include Gaming, Data Center (56% of FY2025 revenue), Professional Visualization, Automotive, and OEM & Others. The surge in AI demand has driven massive sales of data center GPUs, with high-end AI servers containing multiple expensive GPUs, making AI and gaming the biggest growth drivers.

AMD has Lagged Nvidia

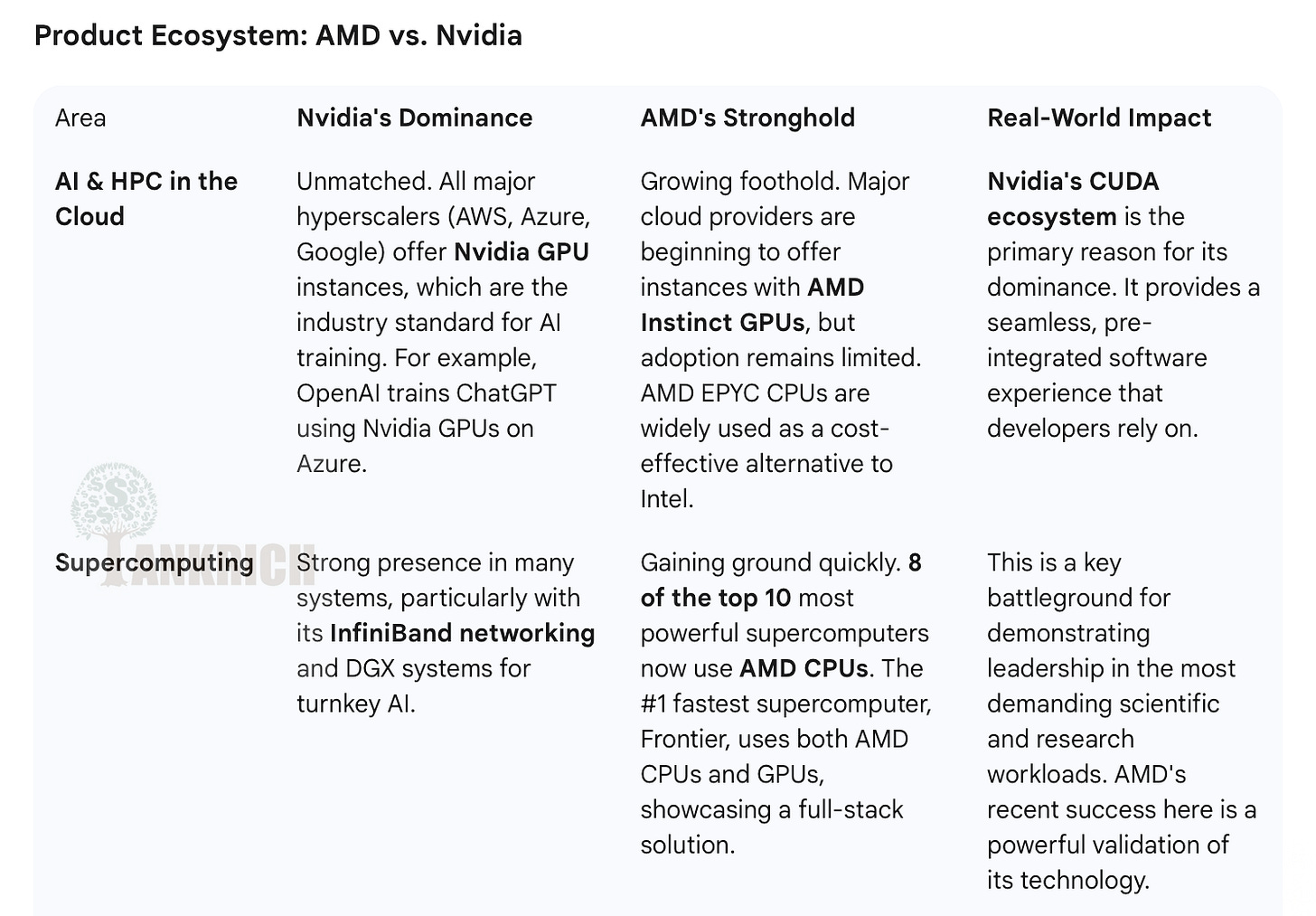

Focused Strategy vs. Diversification:

Nvidia focused solely on GPUs and built a strong software ecosystem (CUDA), allowing rapid innovation. AMD split its efforts between CPUs and GPUs (especially post-2006 ATI acquisition), diluting R&D. This led to Nvidia beating AMD to market with key GPU technologies, like unified shader architecture and GPU compute.Software Ecosystem (CUDA Moat):

Nvidia’s CUDA became the industry standard for GPU programming, creating a network effect that locked in developers and customers. AMD’s alternatives (OpenCL, ROCm) lagged in maturity and adoption, making it hard to compete in AI workloads where Nvidia’s software dominance kept customers loyal.Execution and Financial Resources:

Nvidia consistently delivered on GPU roadmaps with high margins (~60%+), funding more R&D. AMD faced execution issues (e.g., delayed Radeon architectures, less polished drivers) and financial struggles (near bankruptcy in 2015), with lower margins (30-40%), limiting its ability to compete until its turnaround.Product Priorities and Market Focus:

AMD prioritized consumer gaming GPUs and console chips, succeeding there but lagging in data center GPUs. Nvidia expanded early into AI and supercomputing, securing major accounts and mindshare.Nvidia holds 80–90% of the data center GPU market

Is Gap is reducing?

Competitive CPU Advantage Feeding GPU Ambitions:

AMD’s CPU success (Ryzen/EPYC) restored financial health, enabling data center GPU wins (e.g., Frontier supercomputer uses AMD CPUs and GPUs). AMD’s integrated CPU+GPU solutions (like MI300 with unified memory) offer unique advantages Nvidia lacks.Increased R&D and Focus on AI:

AMD boosted R&D (~$6.5B in 2024) and improved ROCm software, promoting open standards like the UltraAccelerator Alliance to challenge Nvidia’s CUDA. Its Instinct MI250/MI300 GPUs generated over $5B in AI revenue in 2024, showing AMD is gaining traction.Market Dynamics and Customer Strategies:

Growing AI demand and concerns about Nvidia dependency open doors for AMD. Cloud providers like Microsoft Azure and Oracle now offer AMD Instinct GPUs, attracted by ~30% price advantages over Nvidia’s equivalents, targeting cost-sensitive AI markets.Closing the Financial Gap:

AMD’s revenue grew to over $25B in 2024 with 50%+ margins, narrowing the R&D gap with Nvidia ($8.7B). Strategic acquisitions (e.g., Pensando) and a stronger talent pool position AMD as a smaller yet credible #2 in data center GPUs, challenging Nvidia’s dominance.

Nvidia’s moat is currently wider anchored by software and sheer dominance in its core market. But AMD is carving niches where Nvidia is weaker (open standards, CPU-GPU integration, custom solutions) and leveraging industry forces that favor multiple players.

We will monitor how successfully AMD can build out its software ecosystem and whether Nvidia can maintain its lock-in if open alternatives gain traction these will determine how durable each company’s moat remains in the coming years.

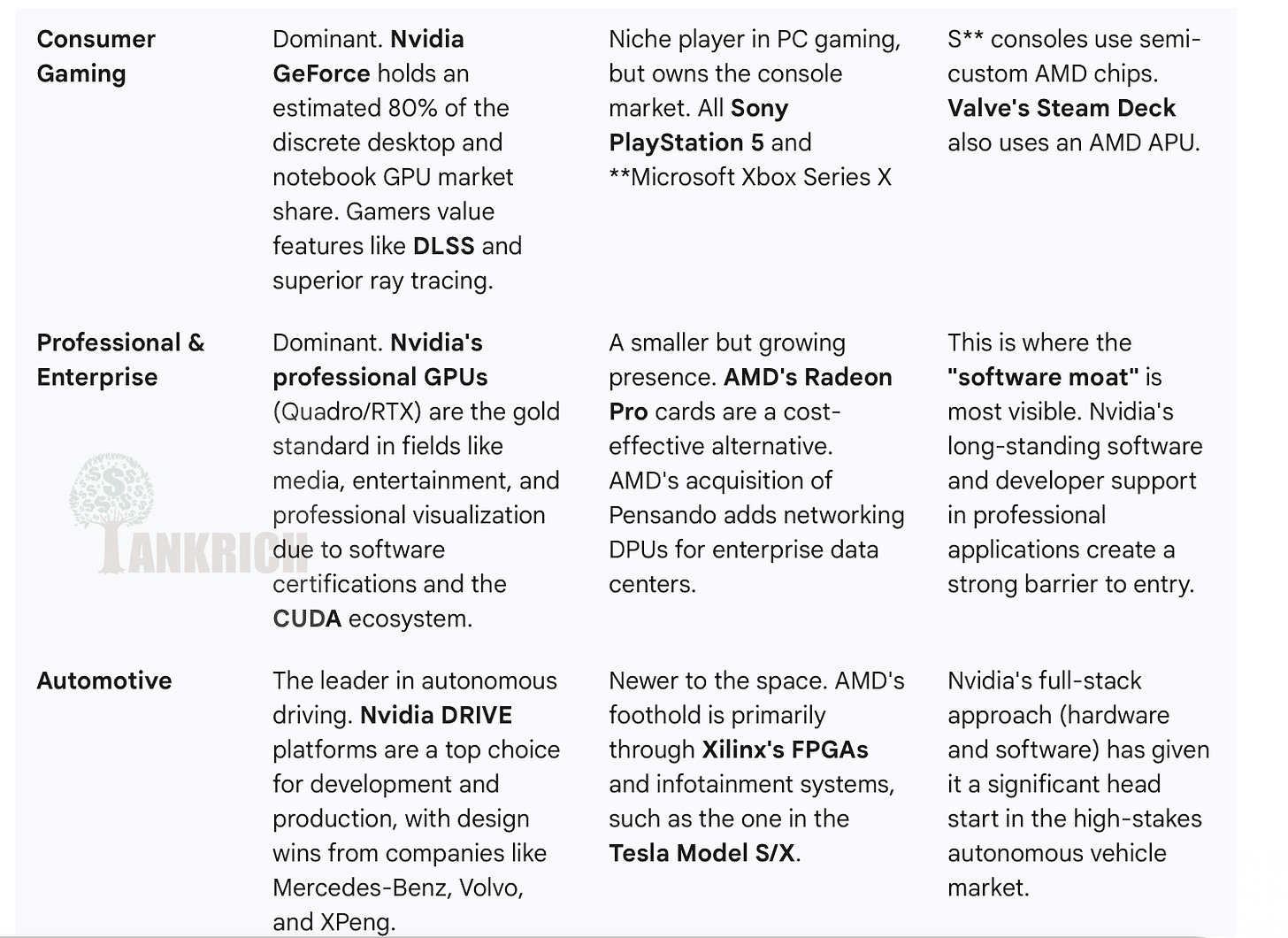

Products and their Roadmap

AMD's roadmap focuses on a consistent cadence of new CPU and GPU architectures, leveraging chiplet technology and integrating AI acceleration across its product lines. Nvidia's strategy centers on the next-generation Blackwell architecture for GPUs, while expanding its platform with integrated CPUs and DPUs to solidify its dominance in the AI and data center markets. Both companies are pushing the boundaries of advanced chiplet packaging and process nodes.

For AMD to seriously compete in this lopsided market there MI350 and MI400 have to deliver and close gap with NVIDIA

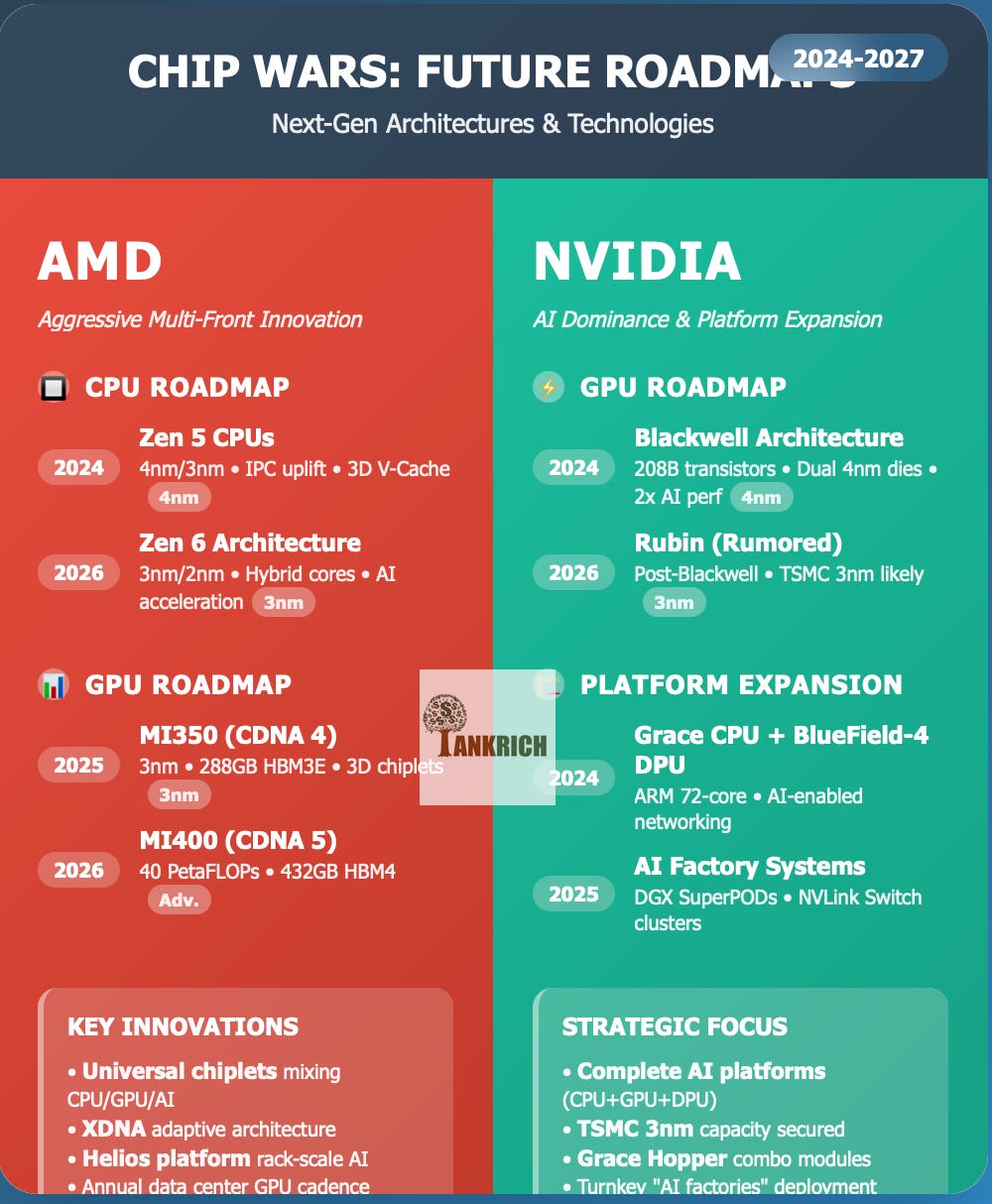

Pricing power and unit economics

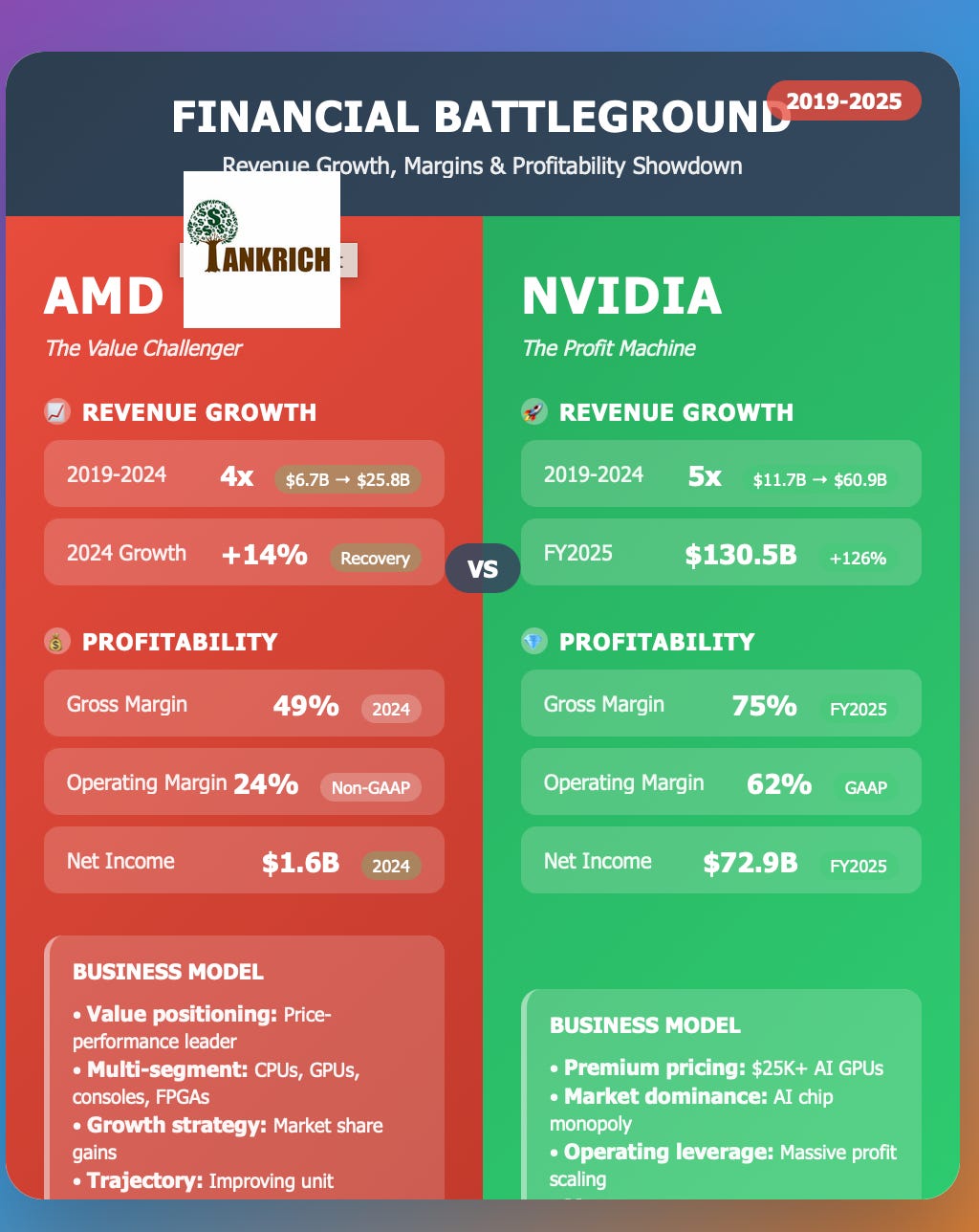

In simpler terms, Nvidia makes more money per chip sold than AMD does. Nvidia’s premium pricing and dominant market share in a high-margin segment (AI chips) means each incremental sale adds substantially to profit. AMD has historically operated with thinner margins and had to price aggressively to win share (especially in CPUs vs Intel and GPUs vs Nvidia).

Looks at huge disparity in below graphic, while both of them had tremendous revenue growth, the margins and profits are poles apart

This pricing power flows into gross profit per unit.

Another unit economics factor: AMD relies on TSMC for wafers just like Nvidia, but Nvidia’s volumes (especially on older nodes for mainstream GPUs) might give it better bargaining leverage or economies of scale. Moreover, Nvidia’s high-end dies, although large, are binned and segmented well they sell cut-down versions as lower models, maximizing yield usage. AMD has gotten better at this (using chiplets to get more dies per wafer and mixing/matching), but Nvidia arguably still runs the most optimized hardware business model in the industry.

However, AMD’s unit economics have been improving: for instance, each EPYC server CPU sold is very lucrative (consider that EPYC chips selling for >$7,000 have Bill of Materials much less, yielding 50%+ margins). As AMD’s revenue mix tilts to these richer segments, its overall unit economics may approach Nvidia’s. AMD’s console chip business, on the other hand, is known to be low margin (console makers aim for cheap BOM), which drags AMD’s average margin but it provides steady volume. This is a trade-off AMD navigates: high-volume, low-margin console and PC sales versus lower-volume, high-margin data center sales. Nvidia has pruned most low-margin business (it even scaled back lower-end OEM chips and focuses on segments where it can earn >60% margin

Manufacturing, Supply Chain, and Facilities

Neither AMD nor Nvidia owns fabrication plants for cutting edge chips. As fabless designers, they are dependent on external foundries, a model with both benefits and risks.

Fabrication (Fabs)

Both companies rely heavily on TSMC (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co.) for advanced node production (7nm, 5nm, 4nm, and 3nm). This reliance exposes them to supply chain risks, including capacity shortages and geopolitical issues related to Taiwan.

Diversification Efforts:

AMD still uses GlobalFoundries for some older chipsets and IO dies, securing supply through a wafer agreement until at least 2025.

Nvidia has previously used Samsung for some products and could consider Samsung's 3nm process for future diversification.

Upcoming Opportunities: The U.S. CHIPS Act is spurring domestic fab construction (e.g., TSMC Arizona and Intel’s foundry services). Both AMD and Nvidia have expressed interest in utilizing these U.S.-based fabs to mitigate geopolitical risk, though this is a long-term prospect.

Packaging and Assembly

After fabrication, chips are sent to OSATs (Outsourced Semiconductor Assembly and Test), located primarily in Taiwan, Malaysia, and China. These partners perform crucial steps like advanced packaging and co-packaging with HBM memory.

Advanced Packaging: Both companies use advanced packaging techniques, such as TSMC’s CoWoS

Capacity Investments: OSATs like Amkor are building new facilities in the U.S. with CHIPS Act support, which could provide domestic packaging options.

Key Facilities and Locations

Both companies maintain major design and engineering centers globally.

AMD: Headquarters in Santa Clara, CA, with major design centers in Austin, TX; Markham, Canada; and a significant, expanding presence in Bangalore, India (with a planned $400 million investment). AMD also inherited facilities from its Xilinx acquisition.

Nvidia: Headquarters in Santa Clara, CA (the "Endeavor" building), with key engineering centers in Bangalore, India; Tel Aviv, Israel (from Mellanox); and research labs in Europe. Nvidia also maintains close ties with TSMC in Taiwan.

Supply Chain Risks and Actions

Both companies must manage shared upstream suppliers for components like memory chips (HBM, GDDR)and substrates.

Capacity Management: Nvidia has made large upfront payments to TSMC to secure wafer capacity, and AMD has similar long-term agreements.

Geopolitical Risks: U.S. export controls have forced Nvidia to create specialized, lower-power versions of its AI chips for the Chinese market. Both companies face the potential for further restrictions and are adapting by diversifying operations and ensuring compliance.

the manufacturing and supply chains for both AMD and Nvidia are defined by their reliance on a small number of key external partners, particularly TSMC.

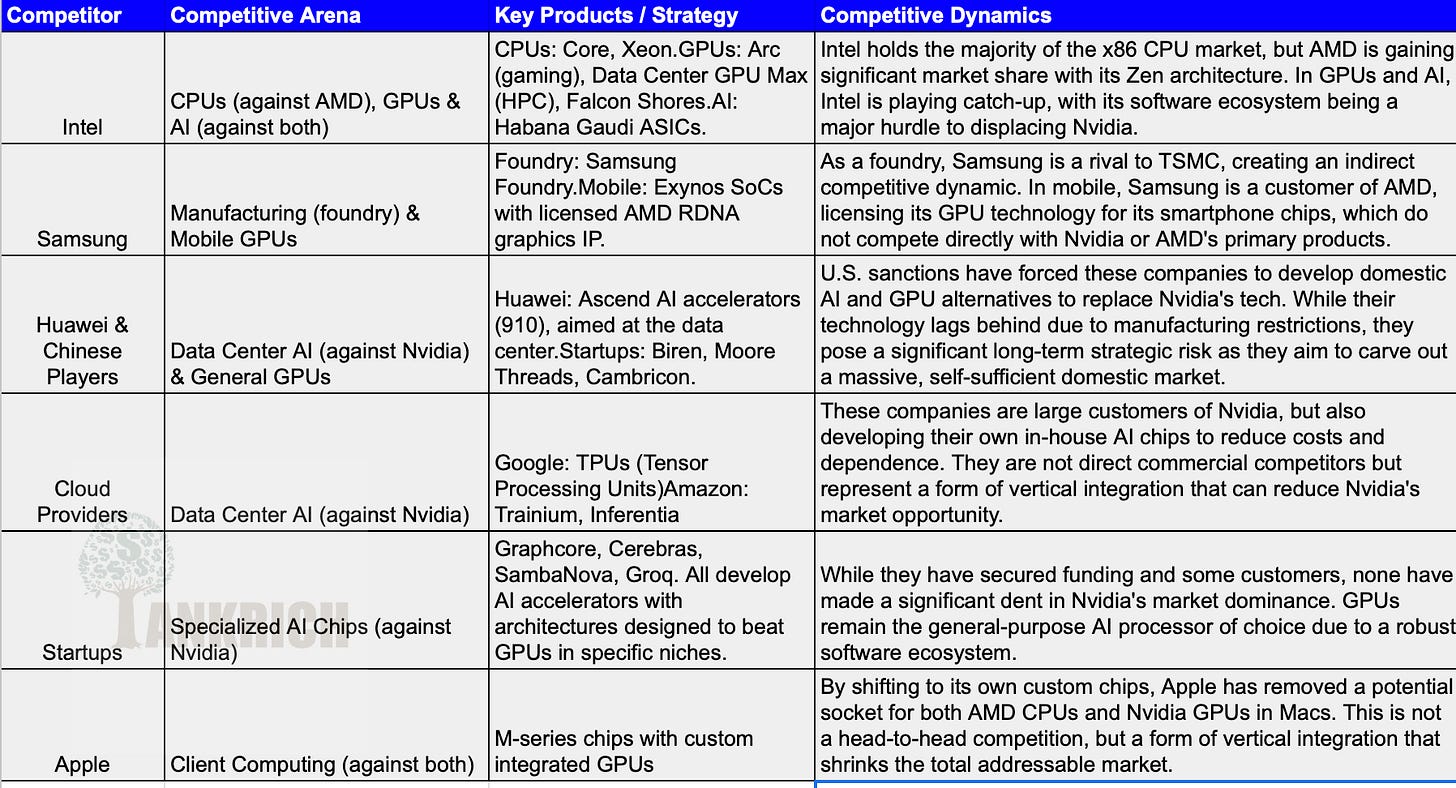

Competitive Landscape

While AMD and Nvidia are often seen as direct competitors, they also face significant challenges from a broader set of players, each with a different approach. For AMD, the main competitor in CPUs is Intel, while in GPUs, it's Nvidia. For Nvidia, the most direct rival is AMD, but it also has to contend with a variety of specialized challengers in the AI and data center space, including cloud giants, startups, and emerging Chinese players

AMD and Nvidia sit at the center of a very competitive industry, with different primary rivals: AMD contends most with Intel in CPUs and with Nvidia in GPUs; Nvidia contends with AMD on GPUs and increasingly with a broad array of newcomers in the AI space. Both must keep innovating aggressively ,Nvidia to fend off the entire world that wants cheaper AI chips, and AMD to keep eroding Intel’s stronghold and to carve a niche against Nvidia. As one wise being puts it, “Nvidia is running so fast it’s lapping others, but AMD has learned to sprint too.”

Thinking about Risks

The complexity of leading edge chips is enormous. Product delays or failures are perennial risks. Nvidia has had relatively smooth launches for a long time, but it’s not immune e.g., it canceled the “GT212” chip a decade ago, had some quality issues with certain mobile GPUs in 2008 (that led to warranty problems). If a new GPU generation hits a snag (yield problems, bugs, etc.), Nvidia could lose its performance crown or miss a cycle (given competitor products arriving). Likewise, AMD’s execution risk is higher in the sense that it’s juggling many product lines (CPU, GPU, FPGA) with a leaner team. The Zen roadmap fortunately has been on track, but the risk remains that a new node (3nm) or new design (like the first hybrid architecture AMD might do) could face unforeseen issues. AMD’s integration of Xilinx also carries execution risk ensuring the FPGA business (where products have long lifecycles) continues to thrive while merging roadmaps with AMD’s vision can be challenging; any culture clash or lost customers in that segment would be a risk.

There’s also risk around new ventures: for Nvidia, entering CPUs (Grace) and becoming a systems provider (offering DGX Cloud) mean new domains where it has less experience, so it might mis execute (e.g., if Grace CPU underperforms vs AMD/Intel, it could flop). For AMD, entering AI at scale if its software isn’t up to par, customers could try MI250 and abandon it, hurting AMD’s credibility in that space long-term. The historical software ecosystem gap is an execution challenge for AMD; it must steadily improve ROCm and developer support. If AMD fails to keep commitment there (as some say it did in the past with earlier GPU compute attempts), it will remain at a disadvantage.

AMD’s strategic vulnerabilities include: the chance of Intel and Nvidia leveraging their respective strengths (process tech, ecosystem, larger scale) to regain ground; AMD’s need to execute flawlessly in multiple domains with comparatively limited resources; heavy reliance on an external fab (TSMC); and being in a market where giants (including new ones like potentially Amazon’s Graviton or Google’s TPU on the CPU side) are all vying for dominance. Lisa Su herself has acknowledged some of these, for example noting that maintaining product leadership is the only way to continue the momentum, and that they cannot become complacent

For both AMD and Nvidia, the focus is on reinvesting for growth, with a secondary emphasis on returning value to shareholders through share repurchases rather than large dividends.

Capital Allocation

Share Buybacks: Both companies prioritize share repurchases over dividends to return capital to shareholders. This strategy is used to offset dilution from stock-based compensation and reduce the total number of outstanding shares. AMD has authorized significant buyback programs, reflecting its improved financial health. Nvidia has also conducted massive share repurchases, including a recent $25 billion authorization, indicating a preference for this method of shareholder return.

Dividends: Neither company pays a meaningful dividend. Nvidia has a token dividend of $0.04 per share, while AMD pays no dividend at all. Both believe that reinvesting profits into research and development (R&D) and strategic acquisitions provides a higher return for shareholders over time.

Balance Sheet & M&A: Both have strong, flexible balance sheets with low debt and billions in cash. This financial strength enables strategic acquisitions. AMD's recent all-stock acquisition of Xilinx and cash purchase of Pensando expanded its product portfolio. Nvidia's successful acquisition of Mellanox and its failed attempt to acquire Arm show its focus on filling strategic gaps and expanding its platform.

Corporate Governance

Leadership: Both companies have a combined CEO-Chair role, with Jensen Huang at Nvidia and Dr. Lisa Su at AMD. While this model can raise governance concerns, both leaders are widely respected for their strategic vision and are considered integral to their companies' success. There is some "key-man risk" associated with their leadership.

Shareholder Alignment: Both AMD and Nvidia use stock-based compensation to attract and retain talent, which can cause dilution. However, they actively use share repurchases to neutralize this effect. This practice aligns employee incentives with long-term shareholder interests.

Culture: Nvidia is known for its founder-led, top-down decision-making culture under Jensen Huang. In contrast, AMD has achieved remarkable stability under Lisa Su after a period of leadership turmoil in the early 2010s, building a reputation for transparent leadership and a disciplined, collaborative approach.

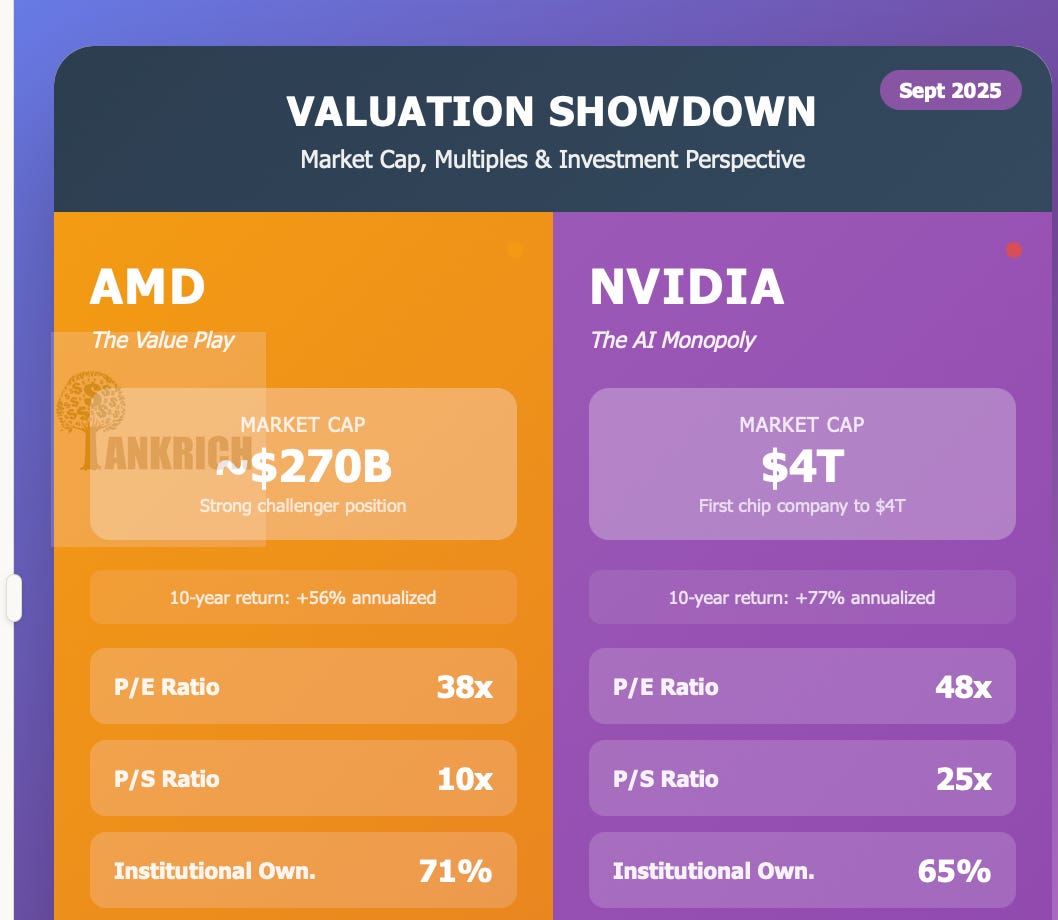

Valuation and Long-Term Owner Perspective

Valuing AMD and Nvidia is challenging given their high growth and the market’s forward-looking optimism, especially for Nvidia amid the AI boom. Let’s frame their valuations in a long-term context

As a long-term holder I will focus on qualitative factors underpinning valuation: moat durability and growth runway. Nvidia’s moat (CUDA, ecosystem) suggests it can earn excess returns longer (justifying a higher multiple), whereas AMD’s moats are narrower, meaning competition (Intel) could compress its margins faster if Intel executes well, which in theory deserves a somewhat lower multiple.

However, AMD is still in a market-share growth phase which can deliver high growth independent of overall market growth (stealing share from Intel yields growth even if the PC market is flat), so owners see good medium-term growth. Once AMD saturates and if it’s splitting market evenly with Intel, growth will then track the overall semi market (~GDP-like plus new markets), which might not justify a very high P/E.

Therefore, an owner must believe AMD can keep expanding into new markets (adaptive, AI) to supplement growth after CPU share gains plateau.

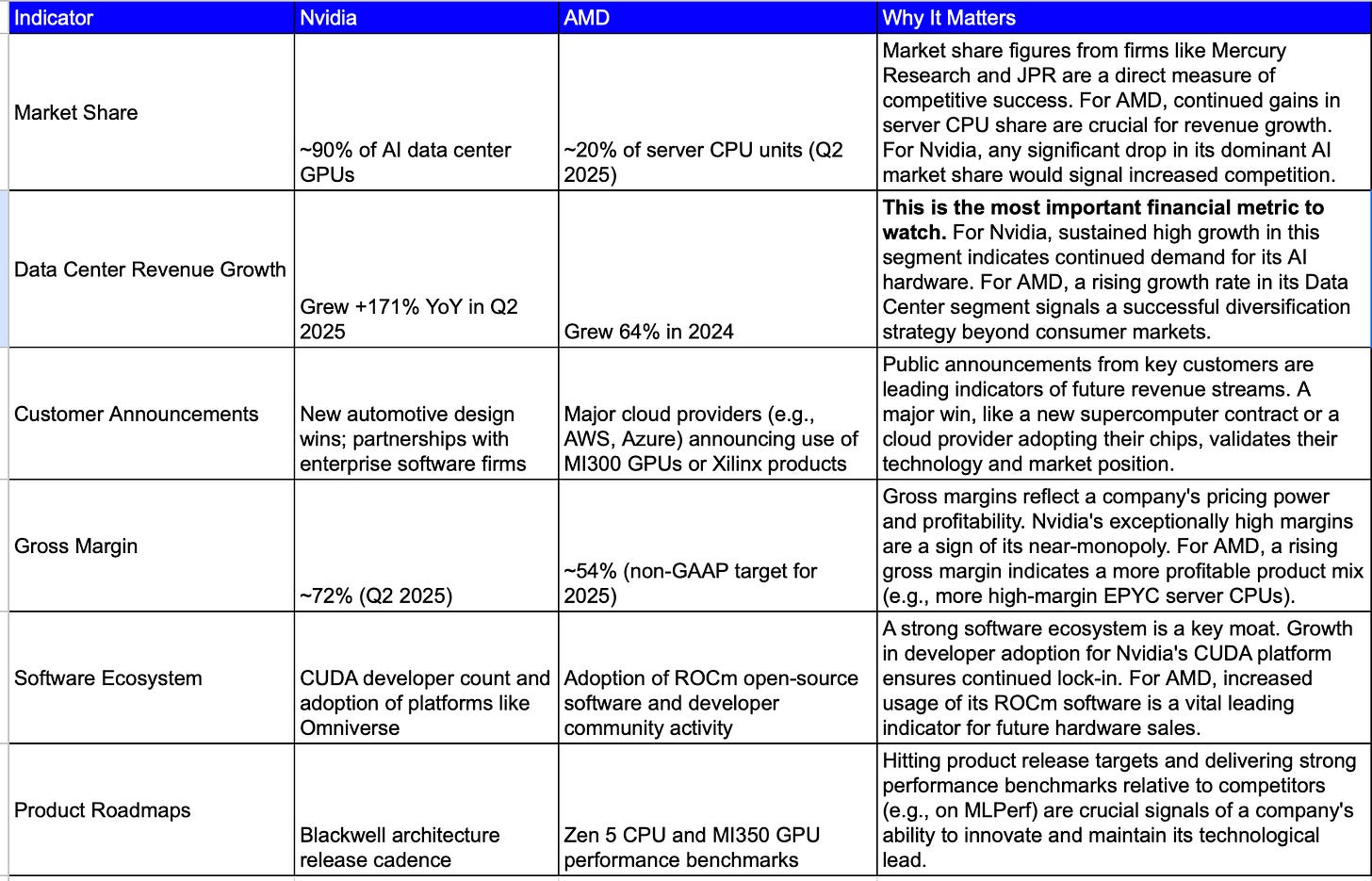

Thinking ahead

Tracking certain leading indicators can provide early signals of how AMD and Nvidia are performing relative to expectations. Here are some of the most pertinent metrics and developments to watch from my perspective

Long term investors like me will be keenly watching those leading indicators >

CPU core roadmaps, AI chip market share, software traction as early signals of how this exciting saga continues. If the last half-decade is any indication, we can expect more twists as AMD and Nvidia push the limits of silicon and strategy in the race for computing dominance. The stakes multi-trillion-dollar industries from cloud to edge could not be higher, making this one of the most important rivalries to watch in tech today.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are for informational and educational purposes only and do not constitute financial, investment, or other professional advice. While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, no guarantee is provided for the completeness or reliability of the information. Readers should do their own due diligence before making any investment decisions.

The author currently owns shares of AMD. This disclosure is made in the interest of full transparency and should not be construed as a recommendation to buy, sell, or hold any securities.